Sci-Ed Update 307

Traffic causes HT, early-bird body clock is Neanderthal, fascia and health, morning sickness cause, diversity helps learning, the art of the syllabus, and more!

The Tissue That Connects Our Muscles May Be a Key to Better Health

Until the early 2000s, doctors believed fascia was just packaging for more important body parts. Since then, researchers have discovered that the connective tissue plays a vital role in how we function and is key to flexibility and range of motion.

Emerging research suggests that caring for your fascia may help treat chronic pain and improve exercise performance and overall well-being.

“We’re still at the very, very beginning” of understanding fascia, said Helene Langevin, the director of the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health at the National Institutes of Health. “This is a part of the body which we have neglected for so long.”

Read more→ AandP.info/u6o

Report: STEM Classes With Racial, Socioeconomic Representation Boost Student GPA

Across science, technology, engineering and math majors, Black, Latino and Native American students initially enroll at similar levels to their white peers but do not complete STEM degrees at the same levels.

There are a variety of factors prior to enrollment that may impact college students’ success, but the college environment can also shape outcomes and equity gaps, according to a new study published in AERA Open, the journal of the American Educational Research Association.

“Despite the presence of a voluminous literature on college student success, one potentially important environmental factor has largely been overlooked: the representation of ingroup peers within college courses,” researchers wrote.

The study, published Dec. 5, analyzed data collected by the College Transition Collaborative, evaluating over 11,800 students at 20 four-year institutions across the nation to measure how greater representation of underrepresented minority and first-generation students could benefit student grades.

Read more→ AandP.info/2wf

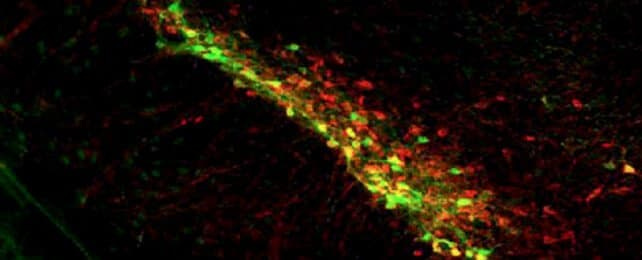

Unexpected Discovery About Dopamine May Help Explain Parkinson's

An investigation led by researchers from Northwestern University in the US has recently uncovered three distinct subtypes of dopamine-reactive neurons in a part of the brain called the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), a region that has roles in processing movement as well as reward responses.

Characterized by individual expression of one of three different genes, each subtype reacts distinctly to either satisfying experiences, unpleasant stimuli, or changes in speed, providing the first solid evidence of dopamine neurons that don't simply reinforce behavior by tickling our pleasure zone.

In some ways, the finding might not come as a complete shock. After all, the substantia nigra is ground zero for Parkinson's disease. A loss of its dopamine-sensitive neurons is associated with the condition's signature symptoms, which include rigidity, slowness, and tremors.

Strangely, the loss of these nerve cells doesn't necessarily result in a loss of rewarding feelings following a successful or joyful task. So it's been unclear until now if the neurons that respond to the hormone generally have more than one job, or if different cells are each responsible for their own function.

Read more→ AandP.info/f59

Extreme morning sickness? Scientists finally pinpoint a possible cause

Researchers have pinpointed a hormone released by growing fetuses that might cause a debilitating form of morning sickness. Women who are more sensitive to the hormone, which increases during early pregnancy, might be at greater risk of experiencing a severe form of nausea and vomiting, called hyperemesis gravidarum, according to the study.

“For the first time, hyperemesis gravidarum could be addressed at the root cause, rather than merely alleviating its symptoms,” says Tito Borner, a physiologist at the University of Pennsylvania. The work was published on 13 December in Nature1.

The finding could also open avenues for treatment. “We now have a clear view of what may cause this problem and a route for both treatment and prevention,” says study co-author Stephen O’Rahilly, a metabolism researcher at the University of Cambridge, UK.

The researchers found that women who had high levels of the hormone GDF15 before they got pregnant had minimal reactions to it while carrying their baby. The findings suggest that giving GDF15 to those at high risk of hyperemesis gravidarum before pregnancy could protect them from the condition. O’Rahilly says that although the study suggests that GDF15 influences the risk of severe sickness, other factors might have a role.

Roughly 70% of women experience nausea and vomiting during pregnancy — colloquially termed morning sickness, even though it can occur at any time of day. Around 0.3–2% experience hyperemesis gravidarum: symptoms so severe that they have difficulty eating, drinking and doing everyday activities. In the worst cases, this can lead to death from dehydration. “It is extremely disabling,” says O’Rahilly.

Read more→ AandP.info/vxj

What's The Deal With That Cough Everyone Seems To Have Right Now?

’Tis the season of respiratory illnesses. As we spend more time indoors and gather with friends and family to celebrate the holidays, cases of flu, COVID and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are steadily increasing around the country.

There’s also been an uptick in anecdotal reports of a brutal, long-lasting cough going around. As one TikTok user put it: everyone seems to have “a hacking cough that’s been going on for weeks.”

Doctors around the country have noticed it, too. “We have been seeing an unusually large number of patients who had typical viral upper respiratory infections, but have had a lingering cough that has lasted weeks to months,” Dr. Scott Braunstein, a double-board certified internal medicine and emergency medicine physician and the national medical director of Sollis Health, told HuffPost.

It doesn’t appear to be the flu or COVID, but another pathogen that’s attacking and irritating our respiratory systems, according to experts.

Read more→ AandP.info/ve6

Early risers may have inherited a faster body clock from Neanderthals

Early risers may have inherited genetic variants from Neanderthals that increased their odds of being morning rather than evening people, new research has found.

While the human body clock is a complex trait shaped by social and cultural norms as well as genetics, Neanderthals, who evolved at high latitudes in Europe and Asia for hundreds of thousands of years, may have been better adapted to seasonal variation in daylight compared with early Homo sapiens, or modern humans, according to a study published Thursday in the journal Genome Biology and Evolution. Early modern humans evolved in latitudes closer to the equator in Africa, where there’s less variation in daylight hours.

It’s possible the adaptation to changes in the amount of daylight was passed on to early Homo sapiens as they moved north out of Africa and encountered and interbred with Neanderthals, who went extinct some 40,000 years ago, the study authors said. And that genetic legacy may still influence variation in the human body clock and chronotype — whether you’re a night owl or a morning lark — today.

Read more→ AandP.info/94u

Does your commute give you high blood pressure? It might be the traffic pollution

Air that’s polluted by traffic exhaust can spike people’s blood pressure sharply almost as soon as they begin traveling, according to a study that monitored people in real time on busy roadways.

The findings — published Monday in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine — suggests that roadway pollution not only poses risks that build up over time, but also that it prompts near-immediate changes to people’s physiology. The study provides some evidence that suggests sitting in traffic could help trigger medical conditions such as heart attacks and strokes, though more research is needed to establish clear links.

The study is the first to measure both pollution and its effect on blood pressure in real time from inside a vehicle as it travels. Researchers monitored both measures dozens of times through traffic in Seattle.

“We were surprised by the magnitude of the blood pressure changes, given the small levels of pollution we measured,” said Dr. Joel Kaufman, a University of Washington professor of medicine, epidemiology and environmental health sciences and an author of the study.

Read more→ AandP.info/a9q

Anatomy & Physiology Syllabus: It’s an Art

Host Kevin Patton discusses the importance of the course syllabus in setting the tone for a course and helping to create a positive course culture. He includes a list of practical, yet artful, steps we can take as we review and update our anatomy and physiology course syllabus.

00:00 | Introduction

02:02 | What, If Anything, Is a Course Syllabus?

13:03 | Sponsored by AAA

14:16 | Sparking a Course Culture

23:58 | Sponsored by HAPI

25:07 | Odds & Ends: Part 1

36:13 | Sponsored by HAPS

37:28| Odds & Ends: Part 2

47:15 | Staying Connected

To listen to this episode, click on the play button above ⏵ (if present) or this link→ theAPprofessor.org/podcast-episode-120.html

Cancer-fighting CAR-T cells could be made inside body with viral injection

Researchers are closing in on ways to produce CAR T cells in the body, raising hopes that the notoriously expensive and bespoke cancer therapies might one day become more accessible.

In CAR-T treatment, immune cells called T cells are removed from the person receiving treatment, engineered to target cancer cells and reintroduced to their body. The process has yielded dramatic recoveries from advanced forms of some blood cancers, but its high price and technical difficulty have placed it out of reach for many people.

Results presented at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in San Diego, California on 11 December suggest that people undergoing treatment might eventually just get an injection of a virus that infects T cells. The virus would then insert the genes needed to guide the T cells to tumour cells.

“You don’t need to take the cells out, you don’t need to purify them,” says John DiPersio, a transplant immunologist and oncologist at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, who says that he was sceptical that the approach would work until he heard the talks at the meeting. “They convinced me that it’s possible.”

Read more→ AandP.info/zxo