Sci-Ed Update 328

Single carbon bonds, microbiome map, obesity drugs for other ailments, many types of cell death, outdated gender language, blood test for lung cancer, promoting integrity, and more!

The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books

…“I think there is a phenomenon that we’re noticing that I’m also hesitant to ignore.” Twenty years ago, Dames’s classes had no problem engaging in sophisticated discussions of Pride and Prejudice one week and Crime and Punishment the next. Now his students tell him up front that the reading load feels impossible. It’s not just the frenetic pace; they struggle to attend to small details while keeping track of the overall plot.

No comprehensive data exist on this trend, but the majority of the 33 professors I spoke with relayed similar experiences. Many had discussed the change at faculty meetings and in conversations with fellow instructors. Anthony Grafton, a Princeton historian, said his students arrive on campus with a narrower vocabulary and less understanding of language than they used to have. There are always students who “read insightfully and easily and write beautifully,” he said, “but they are now more exceptions.”

Read more→ AandP.info/hv5

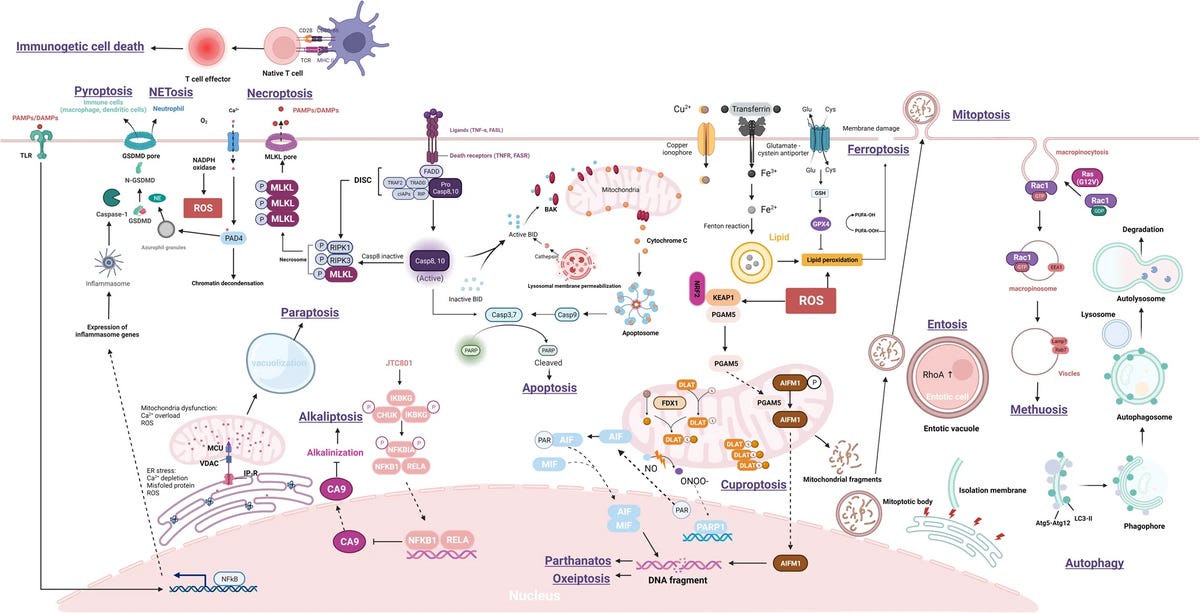

Your cells are dying. All the time.

Billions of cells die in your body every day. Some go out with a bang, others with a whimper.

They can die by accident if they’re injured or infected. Alternatively, should they outlive their natural lifespan or start to fail, they can carefully arrange for a desirable demise, with their remains neatly tidied away.

Originally, scientists thought those were the only two ways an animal cell could die, by accident or by that neat-and-tidy version. But over the past couple of decades, researchers have racked up many more novel cellular death scenarios, some specific to certain cell types or situations. Understanding this panoply of death modes could help scientists save good cells and kill bad ones, leading to treatments for infections, autoimmune diseases and cancer.

Read more→ AandP.info/6i6

Why do obesity drugs seem to treat so many other ailments?

…in a small room at the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), scientists are harnessing the taproom ambience to study whether blockbuster anti-obesity drugs might also curb alcohol cravings.

…Evidence is mounting that they could. Animal studies and analyses of electronic health records suggest that the latest wave of weight-loss drugs — known as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists — cut many kinds of craving or addiction, from alcohol to tobacco use.

Curbing addiction isn’t the only potential extra benefit of GLP-1 drugs. Other studies have suggested they can reduce the risk of death, strokes and heart attacks for people with cardiovascular disease1 or chronic kidney ailments2, ease sleep apnoea symptoms3 and even slow the development of Parkinson’s disease4. There are now hundreds of clinical trials testing the drugs for these conditions and others as varied as fatty liver disease, Alzheimer’s disease, cognitive dysfunction and HIV complications…

Read more→ AandP.info/ldp

Anatomy of Trust: Promoting Integrity in A&P Education

Episode 146 of The A&P Professor podcast is one of our winter shorts, where I replay interesting segments from previous episodes. In this one, we discuss the importance of academic integrity in the Anatomy & Physiology course. We emphasize the need to incorporate discussions about integrity in the syllabus and course materials and share real-life examples of violations in the healthcare field. We highlight how dishonesty can have serious consequences and discuss strategies for prevention, such as using multiple test versions and unique topics for papers/projects. Providing examples of acceptable practices and discouraging unethical behavior foster a culture of integrity. We invite listeners to contribute their own strategies for promoting academic integrity.

00:00 | Introduction

01:07 | Academic Integrity in Anatomy & Physiology

29:39 | Modeling Professional Integrity

38:34 | Staying Connected

To listen to this episode, click on the play button above ⏵ (if present) or this link→ theAPprofessor.org/podcast-episode-146.html

First Gut Microbiome Map for Personalized Food Responses

A recent study has mapped how molecules in food interact with gut bacteria, revealing why people respond differently to the same diets. By examining 150 dietary compounds, researchers found that these molecules can reshape gut microbiomes in some individuals, while having little effect in others.

This breakthrough could enable personalized nutrition strategies to better manage health risks. The findings offer a deeper understanding of the gut microbiome’s role in health and disease.

Key Facts:

Gut bacteria respond differently to the same food molecules in different people.

The study mapped 150 food compounds’ effects on gut microbiomes.

This research could lead to personalized dietary recommendations for better health.

Read more→ AandP.info/xwp

Carbon bond that uses only one electron seen for first time: ‘It will be in the textbooks’

For a little more than a century, chemists have believed that strong atomic links called covalent bonds are formed when atoms share one or more electron pairs. Now, researchers have made the first observations of single-electron covalent bonds between two carbon atoms.

This unusual bonding behavior has been seen between a few other atoms, but scientists are particularly excited to see it in carbon, the basic building block of life on Earth and the key component of industrial chemicals including drugs, plastics, sugars and proteins. The discovery was published1 in Nature on 25 September.

“The covalent bond is one of the most important concepts in chemistry, and discovery of new types of chemical bonds holds great promise for expanding vast areas of chemical space,” says University of Tokyo chemist Takuya Shimajiri, who was part of the carbon bonding research team.

Kevin Patton comment→ It may “be in the textbooks” going forward, but probably not in A&P textbooks.

Read more→ AandP.info/0xo

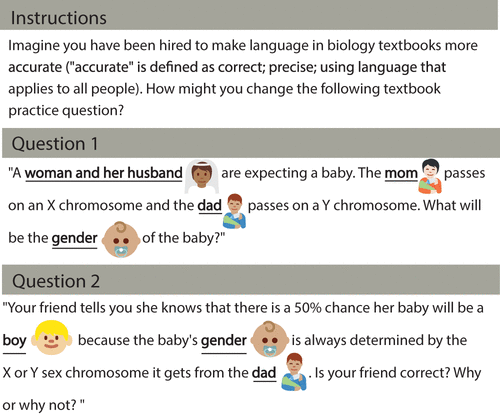

How Do Students Critically Evaluate Outdated Language That Relates to Gender in Biology?

Cisheteronormative ideologies are infused into every aspect of society, including undergraduate science. We set out to identify the extent to which students can identify cisheteronormative language in biology textbooks by posing several hypothetical textbook questions and asking students to modify them to make the language more accurate (defined as “correct; precise; using language that applies to all people”).

First, we confirmed that textbooks commonly use language that conflates or confuses sex and gender. We used this information to design two sample questions that used similar language. We examined what parts of the questions students modified, and the changes they recommended.

When asked to modify sample textbook questions, we found the most common terms or words that students identified as inaccurate were related to infant gender identity. The most common modifications that students made were changing gender terms to sex terms. Students’ decisions in this exercise differed little across three large biology courses or by exam performance.

As the science community strives to promote inclusive classrooms and embrace the complexity of human gender identities, we provide foundational information about students’ ability to notice and correct inaccurate language related to sex and gender in biology.

Kevin Patton comment→ A few comments… This article is a definite must-read for A&P faculty. I think the newer editions of bio and A&P texts probably are (or soon will be) much better about this than those from just five years ago. Cisheteronormative, now that I can say it out loud without stumbling, is being added to my list of favorite multisyllabic terms. But isn’t there a simpler way to express the concept? In the meantime, I’m considering adding it to my LinkedIn profile.

Read more→ AandP.info/1bw

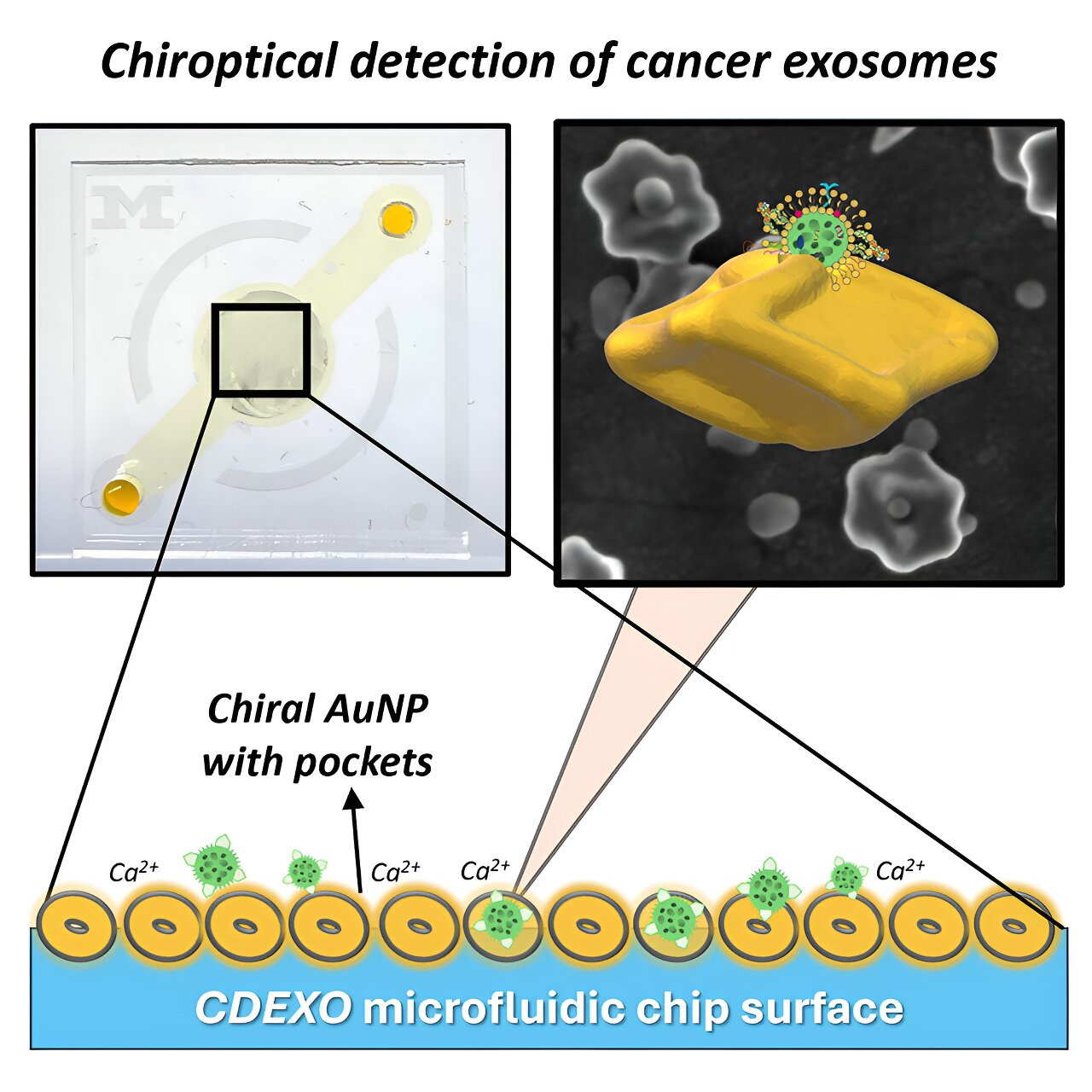

New microchip captures exosomes for faster, more sensitive lung cancer detection from a blood draw

A new way of diagnosing lung cancer with a blood draw is 10 times faster and 14 times more sensitive than earlier methods, according to University of Michigan researchers.

The microchip developed at U-M captures exosomes—tiny packages released by cells—from blood plasma to identify signs of lung cancer.

Once thought to be trash ejected from cells for cleanup, researchers have discovered in the past decade that exosomes are tiny parcels containing proteins or DNA and RNA fragments that are valuable for communication between cells. Although healthy cell exosomes move important signals throughout the body, cancer cell exosomes can help tumors spread by preparing tissues to accept tumor cells before they arrive.

"Cancer exosomes leaving the tumor microenvironment go out and kind of prepare the soil. Later, the cancer cell seeds are shed from the tumor and travel through the bloodstream to plant in the conditioned soil and start to grow," said Sunitha Nagrath, U-M professor of chemical and biomedical engineering and co-corresponding author of the study in the journal Matter.

Read more→ AandP.info/ozv

An mRNA vaccine protected mice against deadly intestinal C. difficile bacteria

Clostridioides difficile is a notoriously nasty intestinal bug, with few effective treatments and no approved vaccines. But the same technology that enabled the first COVID-19 vaccines has shown early promise, in mouse experiments, against this deadly infection, which kills 30,000 people in the United States each year.

An mRNA vaccine designed to target C. difficile and the toxins it produces protected mice from severe disease and death after exposure to lethal levels of the bacterial pathogen, researchers report in the Oct. 4 Science. While it will take much more research to see whether the vaccine is safe and effective for humans, the results hint that an mRNA vaccine might succeed where more conventional vaccines have failed.

Read more→ AandP.info/kyg